Children in the Fire: A Film That Reminds the World Why It Must Wake Up

When the lights go out in a large movie theater, a girl appears on the screen, looking up at the sky. There are no explosions or shelling sounds — yet in her gaze lies the weight of loss, a destroyed home, and shattered dreams. From the very first moments, you begin to understand: this is no longer someone else’s war. This is what it looks like when a fragile child’s life is thrown into the grinder of history.

If there were any temptation to heighten emotion through artistic fiction, here it would be unnecessary. In Children in the Fire, director Evgeny Afineevsky places the viewer in a clear and painful position: the child is at the center, and the war surrounds her. She is a person — one who speaks, suffers, and hopes. That is why this film matters especially for American audiences, who have grown used to perceiving the war as a sequence of numbers and headlines.

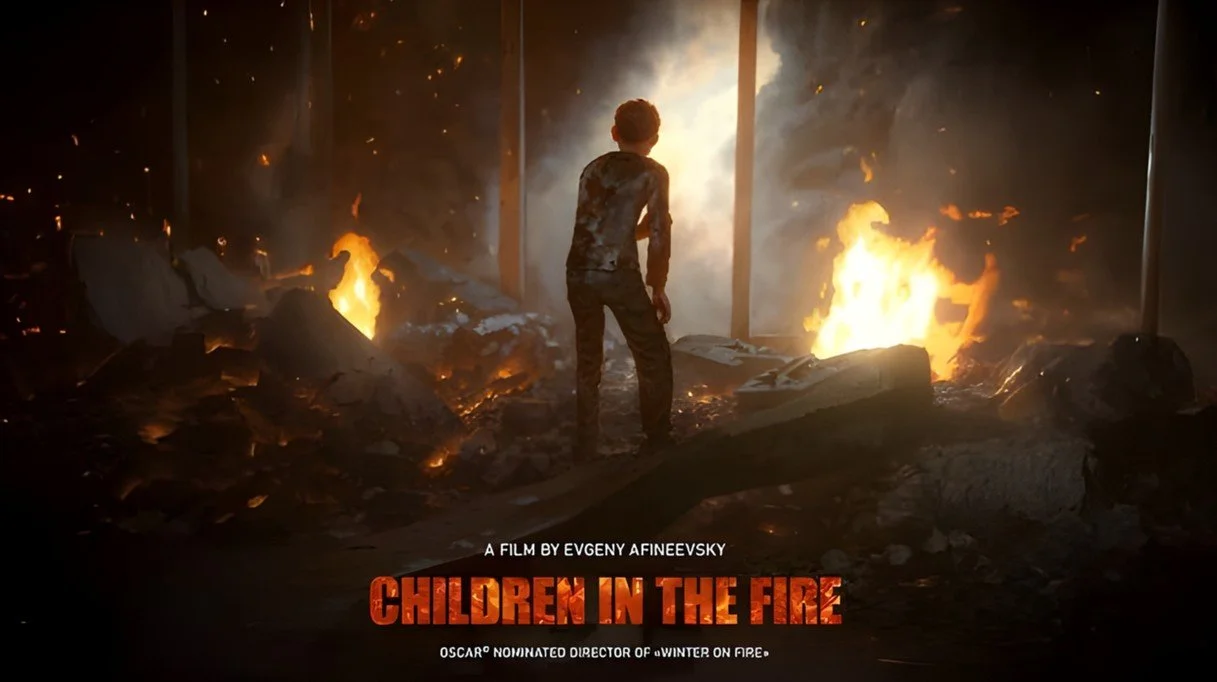

Children in the Fire is a documentary-animated film in which eight Ukrainian children tell their stories — of injuries, abductions, the loss of their homes, and the daily trials they must endure. The 108-minute film had its world premiere at the Raindance Film Festival in London. During the Ukrainian gala premiere at the Odesa International Film Festival, the young protagonists themselves were present, as well as an audience that could feel the temperature of pain.

When a film like this appears in the program of an international festival, it becomes part of a broader global discussion — about what war means when children become its targets. At the Mill Valley Film Festival, Children in the Fire will be featured in the Valley of the Docs section. The North American screening is an opportunity to present this story not to “our own,” but to new audiences — those who may not yet see the full depth of the tragedy amid the daily flow of news, but who can feel it through a single human face.

Looking at these stories, one is struck by how distorted our reality has become. The world keeps talking about the “civilian population,” abstracting away from the individuals who make up that phrase. In Afineevsky’s film, this abstraction dissolves into the small, trembling voices of Yana, Roman, Valeria, and others. Each story is a voice crying out: I am broken — but I am still here.

The world today faces new forms of cruelty: not just missile strikes on cities, but systematic attempts to abduct, re-educate, and erase childhood itself. Dozens of children now live with both physical and psychological scars. What is lost is not only health but also memory, safety, and the feeling of a home that once held them together.

In the United States, wars often feel distant, almost unreal. News reports speak in numbers — of casualties, of destroyed infrastructure, of statistics that remain impersonal. Children in the Fire is an emotional reminder to our collective conscience: war breaks hearts, especially the most fragile and sensitive ones — children’s.

When we speak of responsibility — of societies, international institutions, humanitarian sponsors — we often lack the images that pierce through the abstractions. Children in the Fire tries to fill that void. None of this would have been possible without its creator and driving force, Evgeny Afineevsky, with whom we spoke on the eve of the California screening.

— Your new film shows children who have lived through the war. American audiences often hear about the front lines or politics, but rarely see the war through a child’s eyes. What do you think this film can change in how Americans perceive the war in Ukraine?

With the war fatigue and other world issues, the American audience is more and more distancing itself from this barbaric war that for eleven years has been taking lives of ordinary people and children in Ukraine. People in the U.S. are focusing on their own political and social issues. But there is one universal human factor that opens hearts, minds, and makes people act — it’s children, who are our future. We are all parents, and each of us wants to see the smile of our child every morning under peaceful, sunny skies. While newspapers and world leaders talk about abducted children, I decided to bring a wide spotlight to all children whose childhood has been barbarically destroyed by this inhumane war. Through the big screen, I wanted to give voice to all these kids. I believe that taking the audience on this emotional war journey, told through my little heroes, can help Americans not only understand what the war in Ukraine really is today, but also see how Russia is trying to destroy the country’s future generation.

— The film includes scenes of deportations, loss, injuries. For Americans, this might recall wars in Vietnam, Iraq, or Afghanistan. Did you deliberately seek parallels to show that war is always a civilian tragedy?

Yes, my movie is about war — but it’s a war against the future of a nation. A war against children, who are the future of Ukraine. I didn’t try to draw direct parallels with those wars, because most Americans never witnessed them from the inside. What I’m trying to show is the true barbaric war of the 21st century, where the imperialistic ambition of one country, through death, abduction, and re-indoctrination, tries to erase the future of another — destroying its people and cultural identity. At the same time, I dedicate this film to every child in the world who is suffering today — from wars or from any other kind of cruelty.

— You are already known to American audiences for Winter on Fire. What was the hardest part of making Children in the Fire, when you had to focus entirely on children? Did you fear it might be too painful for Western viewers?

The American and world audiences know my Oscar- and Emmy-nominated film Winter on Fire: Ukraine’s Fight for Freedom. They also know my next film, Freedom on Fire, which I directed and produced right after the full-scale invasion began in 2022. Both films gave a true voice to the Ukrainian people and took audiences deep into their journeys — from Maidan 2013–2014 to the war that followed. During Freedom on Fire, I already recorded the remarkable, resilient voices of Ukrainian kids.

In 2023, I came to the First Lady of Ukraine, Mrs. Olena Zelenska, and to Mr. Dmytro Lubinets — Ukraine’s Human Rights Commissioner — and offered to make a film giving voice only to children. I received an immediate green light. They connected me with key people and organizations whose work today is entirely devoted to saving and rehabilitating children. The list is huge, and all are committed to this cause.

My biggest challenge was emotional. Having PTSD myself and being a parent, it was almost impossible to process the cruelty that these kids went through. But their resilience and unbroken spirit became my inspiration. The pain I experienced, I believe, can help Western audiences wake up and take action — to help end this war and bring the abducted children back home.

— The film includes animated sequences — a powerful artistic choice. For many Americans, animation is associated with children’s films. Why did you choose this form for such a serious and tragic topic?

We’ve all been kids, and we all watched animation — it brings us back to childhood. I wanted to take my audience back there, to childhood in the middle of war. I didn’t want to show another set of horrific news footages that people have grown tired of. I wanted to show the world of war through the child’s own eyes — to take viewers into the experience of a child living through the atrocities of the 21st century.

— You say these children are “a reflection of a great nation.” What qualities of Ukraine do they embody? What can the world learn from them?

In Freedom on Fire, I began with a stand-up comedy scene in a bomb shelter. We saw young Ukrainians joking and laughing about the enemy even as bombs fell above them. That was my reflection on the youth I met on Maidan and saw again during the war. Ukrainians can take a bullet in the face from the enemy, but they will never kneel. They would rather die standing with a smile than bow to the enemy. This same unbreakable spirit you can see in the children of my film — their strength, faith in victory, loyalty to their homeland, and hope for a peaceful future. The world can learn from them — resilience and human dignity. The younger generation everywhere is searching for role models. These kids are exactly that.

— The Kyiv premiere gathered diplomats, human rights defenders, and the public. Do you see the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. as a continuation of that mission — to become the voice of these children here?

The Odesa International Film Festival Gala premiere of Children in the Fire was attended by Dmytro Lubinets, Ukraine’s Human Rights Commissioner; Serhii Kyslytsia, First Deputy Foreign Minister; Mariana Betsa, Deputy Minister; over 30 ambassadors and representatives of foreign missions; members of Parliament; Ukrainian filmmakers, military, and, of course, the children featured in the film. I believe the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S. can continue this mission — by helping to spread this “voice of the children” everywhere: in communities, universities, churches, and among American friends of Ukraine.

— The film has already received several international awards. But awards are one thing; influence on politics or public opinion is another. What real impact do you hope to see from the U.S. screenings?

Awards and recognition only prove the quality of the movie, but more importantly they bring spotlight and create a call to action. All my films are calls to action. Children in the Fire has already been screened at the UK Parliament, where members were so moved that some bills were passed afterward. Congressman Michael McCaul, a great friend of Ukraine, was deeply affected and plans to introduce a new legislative bill. Senator Amy Klobuchar and her team are organizing a bipartisan screening on Capitol Hill this month. If the Ukrainian diaspora continues this mission — spreading the kids’ voices, organizing screenings for key communities — we will see real changes. The voice of children can melt hearts and make adults act.

— The war in Ukraine is often presented through numbers: the number of shellings, injuries, or destroyed targets. Your film is about faces. How might this change Americans’ sense of their country’s responsibility?

While working on the movie, I collaborated with Pope Francis. He met some of my hero-protagonists in the Vatican. When I showed him parts of the film, he said to me: “Children are not numbers. They have faces. Names. Stories. And each one is sacred.” These words became my compass. The Pope also taught me not to label people. Americans who proudly call themselves citizens of this country need to wake up — open their minds and hearts, and be ready to act. On Maidan, I once saw a poster with a single drop of water on it. Below it read: ‘Each of us is a drop of water. But together, we are an ocean.’

Why it matters to be there

When you see these faces on the screen, hear the children’s voices, and feel the weight of silence between their words, you realize this film does not seek sensation. It seeks to capture a moment: that the war today lives inside every Ukrainian child’s heart.

At Mill Valley, the screening will be a meeting with those whose stories are still unheard in this part of the world. It is a chance for Americans to see a war that has reached far beyond the front lines — into the lives of children. By listening to them, we may change how we see, decide, and act. I hope that after this screening, people will not leave the theater indifferent. Someone will remember it months or years later. Someone will tell others. Someone will organize a screening at their university or community center. And it will happen not because of pathos or politics, but because of a simple, uncompromising desire — to give voice to those who are not being heard.

Official trailer: